When working on Lockbox, a demonstration application for compiler-based Stack Erase (a security measure – talk / slides), I wanted to be able to demonstrate in an obvious way that code execution on the device has been obtained. One way to do this is to write a shellcode that prints a message to the LCD display. This can be done with just a few instructions, because we can reuse functions in the program being exploited. All the shellcode needs to do is to call the LCD printing functions with suitable parameters – a pointer to the LiquidCrystal instance, and arguments to the method being called. Some RISC-V assembly code that does this is:

shellcode:

# Call lcd.setCursor(int row, int column)

li a2, 0 ; Set column = 0

li a1, 0 ; Set row = 0

li a0, 0x80000444 ; LiquidCrystal instance (the "this" pointer)

li a5, 0x20401E08 ; LiquidCrystal.setCursor() code address

jalr ra, a5 ; Call function with args in registers

# Call lcd.print(const char* str)

li a0, 0x80000444 ; LiquidCrystal instance

lla a1, pwstr ; Load address of the string to print

li a5, 0x20402c62 ; LiquidCrystal.print() code address

jalr ra, a5 ; Call function with args in registers

pwstr:

.ascii "pwned\n" ; A string to be printed

We can assemble this code:

riscv64-unknown-elf-as -march=rv32imac shellcode.s -o shellcode.obut the assembler output cannot be used as-is – if we dump the assembled code using objdump (with -d for disassemble, and -r for printing relocations):

riscv64-unknown-elf-objdump -dr shellcode.oThen we get the following disassembly (edited slightly for clarity):

00000000 <shellcode>:

0: 4601 li a2,0

2: 4581 li a1,0

4: 80000537 lui a0,0x80000

8: 44450513 addi a0,a0,1092 # 80000444

c: 204027b7 lui a5,0x20402

10: e0878793 addi a5,a5,-504 # 20401e08

14: 000780e7 jalr a5

18: 80000537 lui a0,0x80000

1c: 44450513 addi a0,a0,1092 # 80000444

20: 00000597 auipc a1,0x0

20: R_RISCV_PCREL_HI20 pwstr

20: R_RISCV_RELAX *ABS*

24: 00058593 mv a1,a1

24: R_RISCV_PCREL_LO12_I .L0

24: R_RISCV_RELAX *ABS*

28: 204037b7 lui a5,0x20403

2c: c6278793 addi a5,a5,-926 # 20402c62

30: 000780e7 jalr a5

00000034 <pwstr>:

34: 7770656e0a64 "pwned\n"

The instructions that refer to absolute addresses, like 0x80000444 (for the LiquidCrystal instance) appear in the disassembly, and are part of the encoding of the instruction. However, the address for pwstr appears to be 0x0 in the disassembly – why?

Relocations

The address of pwstr will depend on where the code will eventually be loaded, and the assembler does not know where this will be – we don’t have this problem for the LiquidCrystal instance and code, because their addresses are absolute in the already-linked Lockbox program.

In a normal build process, the assembler generates machine code with placeholders where the linker needs to insert addresses once it has determined them (a.k.a Relocations). During linking, the linker places all symbols in the output object, which assigns them addresses in memory. It can then fix up the relocations using these actual addresses.

In the above dump, R_RISCV_PCREL_HI20 and R_RISCV_PCREL_LO12_I are the relocation types that are used for the address of pwstr – on RISC-V, a 32-bit address is loaded as a combination of two instructions, first loading the upper 20 bits into a register then adding the lower 12 bits. The different relocation types specify different methods for calculating the bits that represent the target address to insert into the instruction encoding. For RISC-V, all relocations are defined in the RISC-V ELF psABI document.

I could have manually worked out what bits needed placing, and hexedited them into the object code. I’d have needed to calculate the distance of the pwstr constant from the PC value when the lla a1, pwstr instruction executes, split out the top 20 and bottom 12 bits, and insert them into the encoded instruction. I wasn’t very keen on doing this, because:

- It would be a little bit fiddly,

- I’d have to manually re-do it every time I changed the shellcode (I didn’t get the above code right first time – it took a few attempts and tweaks), and

- I’d probably make a mistake 50% of the time I did it by hand anyway.

Automation with the linker

So, rather than struggle with this, the GNU Linker can be used to automate this task, because it is controlled by a script that tells it how to place symbols – the purpose of the script is to enable it to emulate a wide range of different linkers, but we can also write a script to automate locating shellcode.

I knew that the exploit would always place shellcode at 0x80003fb, so the trick was to write a linker script that would accept the shellcode, and place it at this location. Then, the output object would have the correct value to load pwstr, and would be ready to write into the target device’s memory without further modification. A linker script that accomplishes this is:

OUTPUT_ARCH( "riscv" )

ENTRY( _start )

MEMORY

{

flash (rxai!w) : ORIGIN = 0x80003fb0, LENGTH = 512M

}

PHDRS

{

flash PT_LOAD;

ram_init PT_LOAD;

ram PT_NULL;

}

SECTIONS

{

.text :

{

*(.text .text.*)

} >flash AT>flash :flash

}

This is a fairly minimal example of a linker script – all it does is define a block of memory (flash) beginning at 0x80003fb0 (ORIGIN = 0x80003fb0), and places all data from the .text section into this memory (the directives inside the SECTIONS command). It doesn’t matter that the memory begins elsewhere (e.g. 0x80000000) with other code and data before where we start linking, because we only need to compute relocations within the shellcode.

When the object code is linked with this script and we disassemble the linked object:

riscv64-unknown-elf-ld -melf32lriscv -Tshellcode.ld shellcode.o \

-o shellcode.exe

riscv64-unknown-elf-objdump -dr shellcode.exethen we see the instructions for loading the address of pwstr (at 0x80003fd0 and 0x80003fd4) have correct values:

... earlier output omitted ...

80003fd0: 00000597 auipc a1,0x0

80003fd4: 01458593 addi a1,a1,20 # 80003fe4 <pwstr>

80003fd0: 00000597 auipc a1,0x0

80003fd4: 01458593 addi a1,a1,20 # 80003fe4 <pwstr>

80003fd8: 204037b7 lui a5,0x20403

80003fdc: c6278793 addi a5,a5,-926 # 20402c62

80003fe0: 000780e7 jalr a5

80003fe4 <pwstr>:

Explanation: the address of pwstr is 20 bytes on from the PC when the auipc instruction executes (0x80003fe4 – 0x80003fd4) so 0 needs adding to the upper 20 bits of the PC, and 20 needs adding to the lower 12 bits.

Not also how in the linked binary, the addresses of all instructions are known, and displayed in the dump. In the original disassembly above, all addresses are relative to the beginning of the object.

Success!

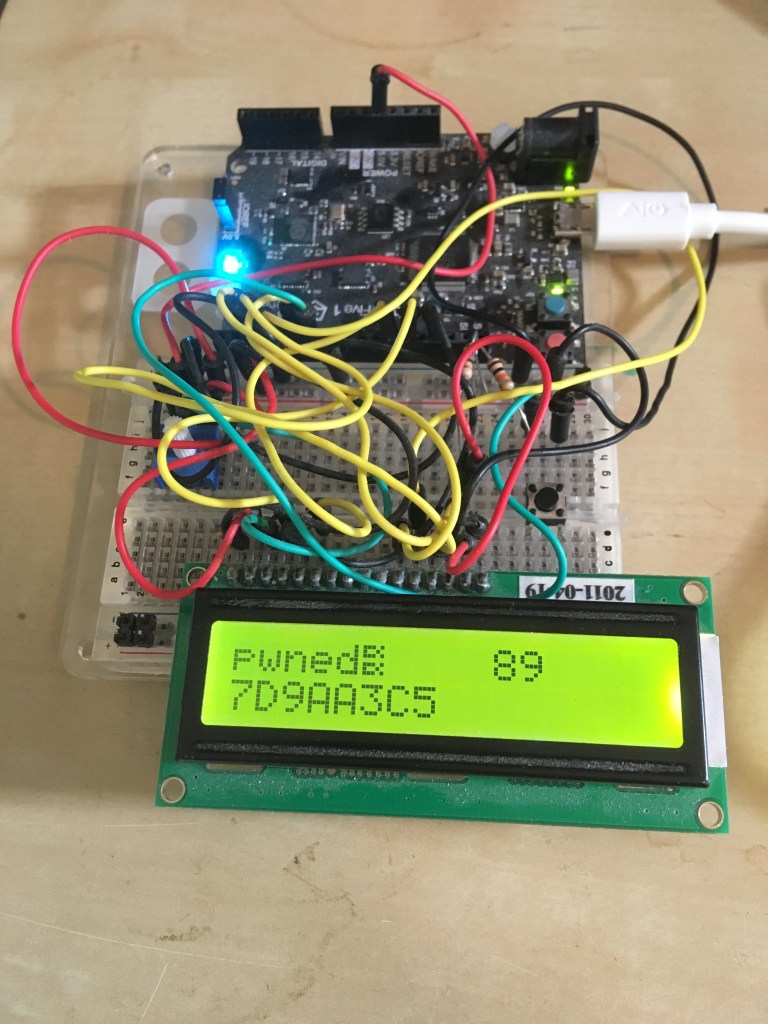

After extracting the .text section from the linked binary and delivering it to the device with the exploit, the result is visible on the display:

Unfortunately I forgot to zero-terminate the string, so there is an “artifact” in the printing – the symbol that looks like two fishes.

Thoughts

The method described above is one way to automate the location of shellcode in a binary – there may be better (perhaps less obtuse, easier to implement) ways to do this for some platforms – I’m not familiar with these methods, as I have limited expertise in shellcoding – I would be interested in hearing if there are better ways of doing things!

That said, this technique can be used on any platform supported by the GNU linker, of which there are quite a few – a list of them can be seen in the directory containing the emulation templates in the source repository – these include (to choose a random few, amongst others) AArch64, Motorola 68000, MIPS, PowerPC, Xtensa, X86, etc… So perhaps if you’re working with a platform with little other tooling (especially for reverse engineering / exploitation), the linker scripting technique may be useful.